What can herring gulls tell us about the health of our seas? As it turns out, potentially quite a lot. Being top predators, seabirds act as conspicuous signals of what is going on beneath the waves, and PhD student Nina O’Hanlon (@Nina_OHanlon)—a member of the institute’s Seabird Interest Group—thinks that the common herring gull could act as an ideal monitor for the quality of marine ecosystems. Here she tells us about her research to track herring gulls during their breeding and non-breeding seasons. By combining their movements with diet, breeding success and environmental information, Nina may be one-step away from turning this seaside pest into an invaluable ally for environmental scientists.

Using herring gulls to monitor the health of coastal marine ecosystems

Coastal marine environments are amongst the most biodiverse and productive habitats, but they have come under increasing pressure from both natural and man-made challenges. Seabirds depend on these habitats for food, and as top predators they reflect what is going on lower down in the food web, providing a means to monitor the health of the local environment. Conspicuous colonies of nesting seabirds are also a lot easier to study than the fish and phytoplankton hidden beneath the sea’s surface.

Before we can use seabirds as monitors, we need to identify a suitable seabird species and track their movements year round. This will allow us to find out whether birds from different colonies rely on different resources—and if they do, is this due to differences in the health of their local coastal environment. To find out, I travelled to Scotland’s dramatic south-west coastline in May last year, where I spent two weeks capturing breeding herring gulls, and enjoying one of the best things about researching seabirds—being out in the field!

So, why the herring gull? To track the health of coastal habitats in south-west Scotland and Northern Ireland we need a seabird that is both common and widespread in the region—the herring gull fits this bill. Herring gulls are opportunists, typically feeding in intertidal areas where they snatch up crabs, sea urchins and mussels as the tide goes out. However, as anyone visiting a busy seaside town may have noticed, many gulls are increasingly feeding inland, stealing people’s chips and ice-creams, as well as scavenging on landfill sites and farmland. But is this behaviour due to their opportunistic nature, accessing an easy and predictable food source? Or it is because their traditional food sources are becoming scarce, potentially indicating that the marine environment is less healthy in these local areas?

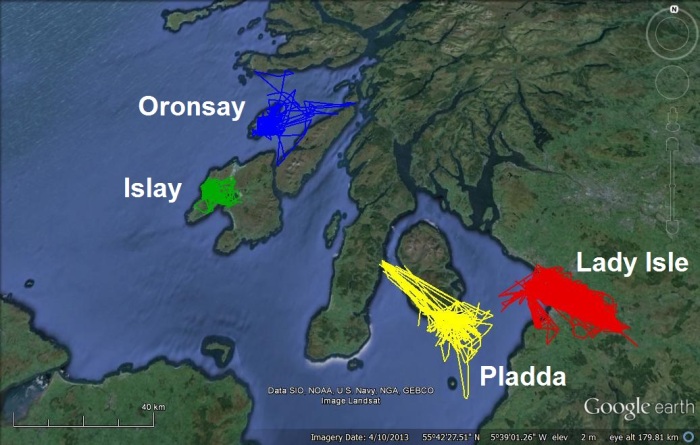

To find out how much time gulls were spending in terrestrial rather than marine habitats, we attached small GPS logging devices on to 25 herring gulls across four locations in south-west Scotland—two colonies in the Firth of Clyde, and two in the Southern Hebrides. To collect the location data, we use a useful piece of kit called a GPS base station—a small box that connects remotely to the GPS loggers on the gulls, allowing us to download the data without re-catching them.

Our first information was for the 2014 breeding season, which revealed some exciting differences between the four colonies. We found that gulls from Lady Isle in the Firth of Clyde spent much of their time on land, visiting towns and landfill sites. In contrast gulls from the more remote Oronsay, in the Southern Hebrides, foraged largely along the coast in the more conventional manner of herring gulls.

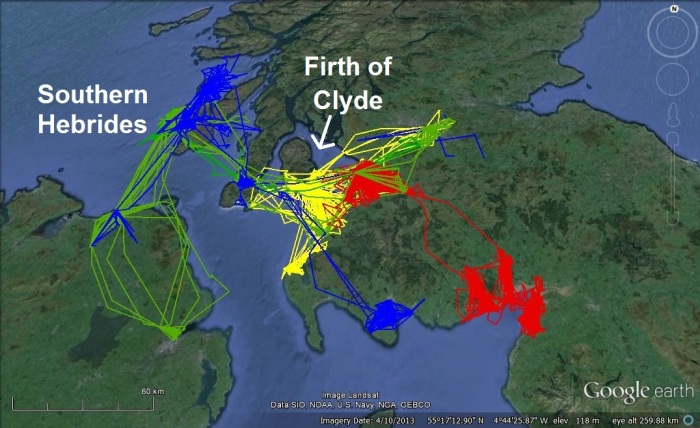

To be a useful monitor of coastal habitats we also need to know where these birds are spending their time outside of the breeding season. For example, if they stay in the same location, does this mean that the marine habitat is sufficiently high quality to support the gulls during the winter? Tracking birds away from the breeding colony is even more exciting, because we know very little about the non-breeding movements of herring gulls—once away from the breeding colony individual birds have traditionally been very difficult to track. Fortunately, recent advances in technology now allow us to track birds year round by using solar powered loggers. So in May this year, it was with some excitement that I headed back to the coast, once again armed with our GPS base station, to re-find our tagged gulls and discover where they had been since leaving the breeding colony last July.

A month later I had over 100,000 positional fixes which I have been eagerly examining to see where the gulls had been. Looking at gull movements from Lady Isle, several birds stayed relatively local, remaining around the Troon area, as they do during the breeding season. However, one bird had moved much further afield, heading south to the Solway Firth and spending some of the winter over the border in Cumbria. The data from the gulls in the Southern Hebrides reveals that they too stayed relatively local for part of the winter. But surprisingly, several of these birds also spent some of the winter south over in Northern Ireland and east into mainland Scotland—overlapping with the Clyde birds.

For gulls in the Firth of Clyde it appears staying local may provide good forage during both the breeding and non-breeding seasons. This does not appear to be the case in the Southern Hebrides. Instead, the Islay and Oronsay gulls head south and east to where they may be able to forage on more predictable resources—whether human derived or more productive coastal habitats—as they are no longer constrained to their nests and chicks on the breeding colonies.

Our new GPS data show that gulls from different colonies do behave differently within and between the breeding season, but so far it cannot tell us whether these differences are due to the health of the environment. However, I also have information on the environment, on the gull’s diet and on each colonies breeding success—by combining these final pieces of the puzzle, I can explore what implications the differences in movement have on the success of the gulls. I can also find out whether the proportion of time they spend in terrestrial versus marine habitats can be used to reflect the health of the local coastal marine environment.

2 thoughts on “Using herring gulls to monitor the health of coastal marine ecosystems”